One of the activities of AI-Ethics.com is to monitor and report on the work of all groups that are writing draft principles to govern the future legal regulation of Artificial Intelligence. Many have been proposed to date. Click here to go to the AI-Ethics Draft Principles page. If you know of a group that has articulated draft principles not reported on our page, please let me know. At this point all of the proposed principles are works in progress.

One of the activities of AI-Ethics.com is to monitor and report on the work of all groups that are writing draft principles to govern the future legal regulation of Artificial Intelligence. Many have been proposed to date. Click here to go to the AI-Ethics Draft Principles page. If you know of a group that has articulated draft principles not reported on our page, please let me know. At this point all of the proposed principles are works in progress.

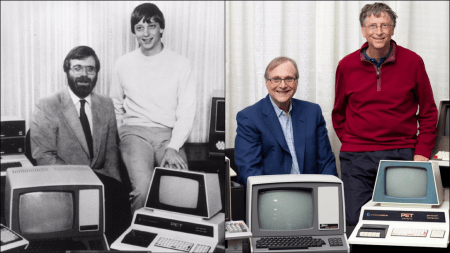

The latest draft principles come from Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. This institute, called AI2, was founded by Paul G. Allen in 2014. The Mission of AI2 is to contribute to humanity through high-impact AI research and engineering. Paul Allen is the now billionaire who co-founded Microsoft with Bill Gates in 1975 instead of completing college. Paul and Bill have changed a lot since their early hacker days, but Paul is still into computers and funding advanced research. Yes, that’s Paul and Bill below left in 1981. Believe it or not, Gates was 26 years old when the photo was taken. They recreated the photo in 2013 with the same computers. I wonder if today’s facial recognition AI could tell that these are the same people?

The latest draft principles come from Oren Etzioni, the CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. This institute, called AI2, was founded by Paul G. Allen in 2014. The Mission of AI2 is to contribute to humanity through high-impact AI research and engineering. Paul Allen is the now billionaire who co-founded Microsoft with Bill Gates in 1975 instead of completing college. Paul and Bill have changed a lot since their early hacker days, but Paul is still into computers and funding advanced research. Yes, that’s Paul and Bill below left in 1981. Believe it or not, Gates was 26 years old when the photo was taken. They recreated the photo in 2013 with the same computers. I wonder if today’s facial recognition AI could tell that these are the same people?

Oren Etzioni, who runs AI2, is also a professor of computer science. Oren is very practical minded (he is on the No-Fear side of the Superintelligent AI debate) and makes some good legal points in his proposed principles. Professor Etzioni also suggests three laws as a start to this work. He says he was inspired by Aismov, although his proposal bears no similarities to Aismov’s Laws. The AI-Ethics Draft Principles page begins with a discussion of Issac Aismov’s famous Three Laws of Robotics.

Oren Etzioni, who runs AI2, is also a professor of computer science. Oren is very practical minded (he is on the No-Fear side of the Superintelligent AI debate) and makes some good legal points in his proposed principles. Professor Etzioni also suggests three laws as a start to this work. He says he was inspired by Aismov, although his proposal bears no similarities to Aismov’s Laws. The AI-Ethics Draft Principles page begins with a discussion of Issac Aismov’s famous Three Laws of Robotics.

Below is the new material about the Allen Institute’s proposal that we added at the end of the AI-Ethics.com Draft Principles page.

_________

Oren Etzioni, a professor of Computer Science and CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence has created three draft principles of AI Ethics shown below. He first announced them in a New York Times Editorial, How to Regulate Artificial Intelligence (NYT, 9/1/17). See his TED Talk Artificial Intelligence will empower us, not exterminate us (TEDx Seattle; November 19, 2016). Etzioni says his proposed rules were inspired by Asimov’s three laws of robotics.

Oren Etzioni, a professor of Computer Science and CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence has created three draft principles of AI Ethics shown below. He first announced them in a New York Times Editorial, How to Regulate Artificial Intelligence (NYT, 9/1/17). See his TED Talk Artificial Intelligence will empower us, not exterminate us (TEDx Seattle; November 19, 2016). Etzioni says his proposed rules were inspired by Asimov’s three laws of robotics.

- An A.I. system must be subject to the full gamut of laws that apply to its human operator.

- An A.I. system must clearly disclose that it is not human.

- An A.I. system cannot retain or disclose confidential information without explicit approval from the source of that information.

We would certainly like to hear more. As Oren said in the editorial, he introduces these three “as a starting point for discussion. … it is clear that A.I. is coming. Society needs to get ready.” That is exactly what we are saying too. AI Ethics Work Should Begin Now.

Oren’s editorial included a story to illustrate the second rule on duty to disclose. It involved a teacher at Georgia Tech named Jill Watson. She served as a teaching assistant in an online course on artificial intelligence. The engineering students were all supposedly fooled for the entire semester course into thinking that Watson was a human. She was not. She was an AI. It is kind of hard to believe that smart tech students wouldn’t know that a teacher named Watson, who no one had ever seen or heard of before, wasn’t a bot. After all, it was a course on AI.

This story was confirmed by a later reply to this editorial by the Ashok Goel, the Georgia Tech Professor who so fooled his students. Professor Goel, who supposedly is a real flesh and blood teacher, assures us that his engineering students were all very positive to have been tricked in this way. Ashok’s defensive Letter to Editor said:

This story was confirmed by a later reply to this editorial by the Ashok Goel, the Georgia Tech Professor who so fooled his students. Professor Goel, who supposedly is a real flesh and blood teacher, assures us that his engineering students were all very positive to have been tricked in this way. Ashok’s defensive Letter to Editor said:

Mr. Etzioni characterized our experiment as an effort to “fool” students. The point of the experiment was to determine whether an A.I. agent could be indistinguishable from human teaching assistants on a limited task in a constrained environment. (It was.)

When we did tell the students about Jill, their response was uniformly positive.

We were aware of the ethical issues and obtained approval of Georgia Tech’s Institutional Review Board, the office responsible for making sure that experiments with human subjects meet high ethical standards.

Etzioni’s proposed second rule states: An A.I. system must clearly disclose that it is not human. We suggest that the word “system” be deleted as not adding much and the rule be adopted immediately. It is urgently needed not just to protect student guinea pigs, but all humans, especially those using social media. Many humans are being fooled every day by bots posing as real people and creating fake news to manipulate real people. The democratic process is already under siege by dictators exploiting this regulation gap. Kupferschmidt, Social media ‘bots’ tried to influence the U.S. election. Germany may be next (Science, Sept. 13, 2017); Segarra, Facebook and Twitter Bots Are Starting to Influence Our Politics, a New Study Warns (Fortune, June 20, 2017); Wu, Please Prove You’re Not a Robot (NYT July 15, 2017); Samuel C. Woolley and Douglas R. Guilbeault, Computational Propaganda in the United States of America: Manufacturing Consensus Online (Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda).

Etzioni’s proposed second rule states: An A.I. system must clearly disclose that it is not human. We suggest that the word “system” be deleted as not adding much and the rule be adopted immediately. It is urgently needed not just to protect student guinea pigs, but all humans, especially those using social media. Many humans are being fooled every day by bots posing as real people and creating fake news to manipulate real people. The democratic process is already under siege by dictators exploiting this regulation gap. Kupferschmidt, Social media ‘bots’ tried to influence the U.S. election. Germany may be next (Science, Sept. 13, 2017); Segarra, Facebook and Twitter Bots Are Starting to Influence Our Politics, a New Study Warns (Fortune, June 20, 2017); Wu, Please Prove You’re Not a Robot (NYT July 15, 2017); Samuel C. Woolley and Douglas R. Guilbeault, Computational Propaganda in the United States of America: Manufacturing Consensus Online (Oxford, UK: Project on Computational Propaganda).

In the concluding section to the 2017 scholarly paper Computational Propaganda by Woolley (shown here) and Guilbeault, The Rise of Bots: Implications for Politics, Policy, and Method, they state:

The results of our quantitative analysis confirm that bots reached positions of measurable influence during the 2016 US election. … Altogether, these results deepen our qualitative perspective on the political power bots can enact during major political processes of global significance. …

Most concerning is the fact that companies and campaigners continue to conveniently undersell the effects of bots. … Bots infiltrated the core of the political discussion over Twitter, where they were capable of disseminating propaganda at mass-scale. … Several independent analyses show that bots supported Trump much more than Clinton, enabling him to more effectively set the agenda. Our qualitative report provides strong reasons to believe that Twitter was critical for Trump’s success. Taken altogether, our mixed methods approach points to the possibility that bots were a key player in allowing social media activity to influence the election in Trump’s favour. Our qualitative analysis situates these results in their broader political context, where it is unknown exactly who is responsible for bot manipulation – Russian hackers, rogue campaigners, everyday citizens, or some complex conspiracy among these potential actors.

Despite growing evidence concerning bot manipulation, the Federal Election Commission in the US showed no signs of recognizing that bots existed during the election. There needs to be, as a minimum, a conversation about developing policy regulations for bots, especially since a major reason why bots are able to thrive is because of laissez-faire API access to websites like Twitter. …

The report exposes one of the possible reasons why we have not seen greater action taken towards bots on behalf of companies: it puts their bottom line at risk. Several company representatives fear that notifying users of bot threats will deter people from using their services, given the growing ubiquity of bot threats and the nuisance such alerts would cause. … We hope that the empirical evidence in this working paper – provided through both qualitative and quantitative investigation – can help to raise awareness and support the expanding body of evidence needed to begin managing political bots and the rising culture of computational propaganda.

This is a serious issue that requires immediate action, if not voluntarily by social media providers, such as Facebook and Twitter, then by law. We cannot afford to have another election hijacked by secret AIs posing as real people.

As Etzioni stated in his editorial:

As Etzioni stated in his editorial:

My rule would ensure that people know when a bot is impersonating someone. We have already seen, for example, @DeepDrumpf — a bot that humorously impersonated Donald Trump on Twitter. A.I. systems don’t just produce fake tweets; they also produce fake news videos. Researchers at the University of Washington recently released a fake video of former President Barack Obama in which he convincingly appeared to be speaking words that had been grafted onto video of him talking about something entirely different.

See: Langston, Lip-syncing Obama: New tools turn audio clips into realistic video (UW News, July 11, 2017). Here is the University of Washington YouTube video demonstrating their dangerous new technology. Seeing is no longer believing. Fraud is a crime and must be enforced as such. If the government will not do so for some reason, then self- regulations and individual legal actions may be necessary.

In the long term Oren’s first point about the application of laws is probably the most important of his three proposed rules: An A.I. system must be subject to the full gamut of laws that apply to its human operator. As mostly lawyers around here at this point, we strongly agree with this legal point. We also agree with his recommendation in the NYT Editorial:

Our common law should be amended so that we can’t claim that our A.I. system did something that we couldn’t understand or anticipate. Simply put, “My A.I. did it” should not excuse illegal behavior.

We think liability law will develop accordingly. In fact, we think the common law already provides for such vicarious liability. No need to amend. Clarify would be a better word. We are not really terribly concerned about that. We are more concerned with technology governors and behavioral restrictions, although a liability stick will be very helpful. We have a team membership openings now for experienced products liability lawyers and regulators.

I have read your piece and I understand your concerns but I think any idea of “AI ethics” and “AI regulation” long left the station. There is an analogy to the arguments that have been made about IT security and the IoT that “must be regulated and the law engaged because the market can’t fix this”.

But as Bruce Schneier and many others have noted about IT security and the IoT, these have simply grown too fast, too global for American law or regulations. The same for AI. Same old story: new technology arrives on the scene, society is often forced to rethink previously unregulated behavior. This change often occurs after the fact, when we discover something is amiss. The speed at which this tech is rolled out to the public can make it hard for society to keep up. When you’re trying to build as big as possible or as fast as possible, it’s easy for folks who are more skeptical or concerned have issues they’re raising left by the wayside, not out of maliciousness but because, ‘Oh, we have to meet this ship date’.

And if you do regulate AI, what regulator?

– Which government? Maybe the United Nations?

– What’s the enforcement mechanism? Is after-the-fact “punishment” feasible?

– What’s the end point of AI regulation? We still have lawyers/regulators trying to fit 2017 tech into 1990 laws.

– And AI moves far too fast. And do you really think you can control the Russians and Chinese who have perfected stealth AI where YOU CANNOT detect who/what is AI or real people?

– And how do you control researchers and developers who release their code on GitHub which allows AI tech to appear/go anywhere?

As far as AI systems clearly disclosing they are not human, and your points about another election hijacked by secret AIs posing as real people, etc. the idea of a free/fair vote in America is history. It is in the past.

Just a few thoughts.

I am just leaving Kiev, Ukraine after a 3-day workshop on Russian cyber strength, part of a 8th month study I have undertaken to get a grip on this, Facebook devil doings, etc. I have had the opportunity these past months to chat with people in the intelligence community, ex-Facebook engineers etc. What the Russians have developed/accomplished is incredible. It requires a much longer post.

One thing you did not note in your post was ProPublica’s revelation … they had A LOT of inside help … that Facebook’s ad tools could target racists and anti-Semites using the very information those users self-report. That initial report kicked off a series of experiments conducted by news organizations that found that Google’s search engine and Facebook’s engine would not only let you place ads next to search results for hateful rhetoric, but its automated processes would even suggest similar, equally hateful search terms to sell ads against.

NOTE: Twitter was also caught up in the controversy, when its filtering mechanisms failed to prevent ads from targeting “Nazi” and the n-word, an issue the company inexplicably attributed to “a bug we have now fixed.” This week, Instagram converted a journalist’s post about a violent threat she received into an ad .. that it then served to the journalist’s contacts.

The most telling comment/response was Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg who said the issue was the result of a failure on the company’s part: “We never intended or anticipated this functionality being used this way — and that is on us. And we did not find it ourselves — and that is also on us.”

As Kevin Roose noted on his blog “Her’s was a candid admission that reminded me of a moment in Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” after the scientist Victor Frankenstein realizes that his cobbled-together creature has gone rogue. “I had been the author of unalterable evils,” he says, “and I lived in daily fear lest the monster whom I had created should perpetrate some new wickedness.”

Facebook is fighting through a tangled morass of privacy, free-speech and moderation issues with governments all over the world. Congress is investigating reports that Russian operatives used targeted Facebook ads to influence the 2016 presidential election. In Myanmar, activists are accusing Facebook of censoring Rohingya Muslims, who are under attack from the country’s military. In Africa, the social network faces accusations that it helped human traffickers extort victims’ families by leaving up abusive videos.

Few of these issues stem from willful malice on the company’s part. It’s not as if a Facebook engineer in Menlo Park personally greenlighted Russian propaganda, for example. On Thursday, the company said it would release political advertisements bought by Russians for the 2016 election, as well as some information related to the ads, to congressional investigators.

But as a Facebook engineer told me “we are a technology company, not an intelligence agency or an international diplomatic corps. Our engineers are in the business of building apps and selling advertising, not determining what constitutes hate speech in Myanmar. And with two billion users, including 1.3 billion who use it every day, moving ever greater amounts of their social and political activity onto Facebook, it’s possible that the company is simply too big to understand all of the harmful ways people might use its products.”

And as a ex-Facebook engineer told me: “This shit is baked in. It’s not only that these ad systems are governed by algorithms, but that the software is increasingly guided by artificial intelligence tools that automate systems in ways even we … the creators … do not fully comprehend.”

But it’s also that, because of their breadth and poor oversight, Facebook and Google have become unvarnished reflections of how humans behave on the internet. Containing and serving that entire spectrum of our interests, no matter how vile, is a feature, not a bug. These companies’ products are measured by their user growth because that is their utility to advertisers. That racism and bigotry would have a place within Silicon Valley’s set of ad-targeting options feels indicative of the industry’s growth-at-all-costs mindset.

And the political ads? I find it somewhat amusing that in 2011, Facebook asked the Federal Election Commission to exempt it from rules requiring political advertisers to disclose who’s paying for an ad. Political ads on TV and radio must include such disclosures. But Facebook argued that its ads should be regulated as “small items,” similar to bumper stickers, which don’t require disclosures. The FEC ended up deadlocked on the issue, and the question of how to handle digital ads has languished for six years.

Now, it’s blowing up again.

And you want to talk about regulation? Let me run this by you, courtesy of Issie Lapowsky who writes about this extensively for Wired Magazine (noted by *) :

*Zuckerberg announced new transparency measures that would require political advertisers on Facebook to disclose who’s paying for their ads and publicly catalog different ad variations they target at Facebook users. Members of Congress, meanwhile, are mulling a bill that would require such disclosures. These would be unprecedented moves, setting new standards for digital political ads. But they likely wouldn’t prevent abuses, largely because of the US’s confusing, loophole-ridden system for regulating political advertising.

*Case in point: Shortly before the 2016 election, the crowdfunding site, WeSearchr, run by the notorious far-right internet troll Chuck Johnson, raised just over $5,000 to put up a billboard in the battleground state of Pennsylvania. The illustration for the billboard showed a sparkling new yellow-brick wall, marked with a sign reading “U.S. Border.” It was guarded at night by two Pepe frogs dressed as Donald Trump, pointing their guns at anyone who attempts to cross their path. The caption, which appeared next to a smiling crescent moon wearing sunglasses, read ominously, “It’s always darkest before the Don…”

*The billboard DID NOT have to mention its funders—many of whom were anonymous. “That would not fall under campaign finance law,” explains Brendan Fischer, director of Federal Election Commission reform at the Campaign Legal Center. “It doesn’t include any expressed advocacy, saying to vote for or against a candidate.”

*In other words, because the Pepe billboard wasn’t purchased by the Trump campaign and didn’t explicitly mention the election, its backers were under no obligation to disclose who paid for it. The same legal gray area would apply on Facebook, but at a much larger—and more dangerous—scale.

*On Facebook, where most ads are sold by machines, the WeSearchr crew could have bought thousands of digital billboards in a matter of minutes. And the volume of these ads sold by machines … all automated … is staggering.

And what about the Russia propagandists who used Facebook to organize more than a dozen pro-Trump rallies in Florida during last year’s election, and this year? Politico noted the demonstrations — at least one of which was promoted online by local pro-Trump activists — brought dozens of supporters together in real life. They were the first case of Russian provocateurs successfully mobilizing Americans over Facebook in direct support of Donald Trump.

It’s difficult to determine how many of those locations actually witnessed any turnout, in part because Facebook’s recent deletion of hundreds of Russian accounts hid much of the evidence. But videos and photos from two of the locations — Fort Lauderdale and Coral Springs — were reposted to a Facebook page run by the local Trump campaign chair, where they remain to this day.

Key point: these “flash mobs” were conceived and organized over a Facebook page called “Being Patriotic” which the data scientists at The Daily Beast identified as accounts in a software-assisted review of politically themed social-media profiles. “Being Patriotic” had 200,000 followers and the strongest activist bent of any of the suspected Russian Facebook election pages that have so far emerged.

My point? This is a far more intractable problem than either Facebook or regulators are letting on. Facebook is so gargantuan, it’s exceeded our capability to manage it.

And, please, let’s forget/ignore Zuckerberg’s little video “mea culpa” chat this week. His PR consultants … he has four PR companies on retainer … have always told him to “control the narrative”. When I was at Cannes Lions this year I spoke to one of his PR consultants and that was the task. So dear Mark talks about the “hacker creed” and adds in his “faux debate” with Elon Musk about AI ethics. Good job, Mark. Keep our eye off the ball.

Facebook did not grow into a $500bn business by being “a force for good in democracy”. Nor was it by “making the world more open and connected” (its first mission statement) and “bringing the world closer together” (its new mission statement). Facebook grew to its current size, influence and wealth by selling advertisements. And it sold those advertisements by convincing users to provide it with incredibly intimate information about our lives so that advertisers could in turn use that information to convince us to do things. Some advertisers want us to buy things. Some want us to attend events. And some want us to vote a certain way. Facebook makes all that advertising cheap and easy and astonishingly profitable by cutting out the sales staff who, in a different kind of company, at a different time, would have looked at an advertisement before it ran.

So listen: Facebook’s systems didn’t “fail” when they allowed shadowy actors connected to the Russian government to purchase ads targeting American voters with messages about divisive social and political issues. They worked. “There was nothing necessarily noteworthy at the time about a foreign actor running an ad involving a social issue,” Facebook’s vice-president of policy and communications, Elliot Schrage, wrote of the Russian ads in a blogpost.

Shortly after the election, Zuckerberg attempted to shrug off the impact of Facebook in Americans’ voting decision, calling the notion that fake news swayed voters a “pretty crazy idea”. But the CEO of an advertising company can’t afford to denigrate the power of advertising too much; his revenues depend on his actual paying customers believing that Facebook can influence behavior.

Instead, Zuckerberg has constructed for himself a worldview in which every good outcome (such as 2 million people registering to vote thanks to Facebook’s advertisements) was intentional, and every bad outcome was just a mistake that can be addressed by tweaking the existing systems.

Screed over. Got to catch a flight.

It is just the early stages yet when you consider what will happen with AI and other technology over the next two decades. I’m obviously more optimistic than you on most things old friend. In today’s greedy political environment it does get more difficult to keep a positive attitude, but I choose to hang onto my ideals. I choose not be too discouraged by the dark side, but instead be motivated to action. Light and love will win in the end, but only by our efforts.

[…] siano state accolte con favore dalla comunità scientifica, queste tre leggi hanno un limite: essere solamente, come scrive lo […]

[…] touched on this danger previously in my blog, New Draft Principles of AI Ethics Proposed by the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence and th… There I cited the scholarly paper with the latest research by Oxford University on what happened in […]