Every lawyer who thinks e-discovery is not important, that you can just delegate it to a vendor, should read Abbott Laboratories, et al. v. Adelphia Supply USA, et al., No. 15 CV 5826 (CBA) (LB) (E.D.N.Y. May 2, 2019). This opinion in a trademark case in Brooklyn District Court (shown here) emphasizes, once again, that e-discovery can be outcome-determinative. If you mess it up, you can doom your case. If a lawyer wants to litigate today, they either have to spend the substantial time it takes to learn the many intricacies of e-discovery, or associate with a specialist who does. The Abbott Labs case shows how easily a law suit can be won or lost on e-discovery alone. Here the numbers did not add up, key custodians were omitted and guessed keywords were used, keywords so bad that opposing counsel called them designed to fail. The defendants reacted by firing their lawyers and blaming everything on them, but the court did not buy it. Instead, discovery fraud was found and judgment was entered for the plaintiff.

Every lawyer who thinks e-discovery is not important, that you can just delegate it to a vendor, should read Abbott Laboratories, et al. v. Adelphia Supply USA, et al., No. 15 CV 5826 (CBA) (LB) (E.D.N.Y. May 2, 2019). This opinion in a trademark case in Brooklyn District Court (shown here) emphasizes, once again, that e-discovery can be outcome-determinative. If you mess it up, you can doom your case. If a lawyer wants to litigate today, they either have to spend the substantial time it takes to learn the many intricacies of e-discovery, or associate with a specialist who does. The Abbott Labs case shows how easily a law suit can be won or lost on e-discovery alone. Here the numbers did not add up, key custodians were omitted and guessed keywords were used, keywords so bad that opposing counsel called them designed to fail. The defendants reacted by firing their lawyers and blaming everything on them, but the court did not buy it. Instead, discovery fraud was found and judgment was entered for the plaintiff.

Magistrate Judge Lois Bloom (shown right) begins the Opinion by noting that the plaintiff’s motion for case ending sanctions “… presents a cautionary tale about how not to conduct discovery in federal court.” The issues started when defendant made its first electronic document production. The Electronically Stored Information was all produced in paper, as Judge Bloom explained “in hard copy, scanning them all together, and producing them as a single, 1941-page PDF file.” Opinion pg. 3. This is not what the plaintiff Abbott Labs wanted. After Abbott sought relief from the court the defendants on March 24, 2017 were ordered to “produce an electronic copy of the 2014 emails (1,941 pages)” including metadata. Defendant then “electronically produced 4,074 pages of responsive documents on April 5, 2017.” Note how the page count went from 1,942 to 4,074. There was no explanation of this page count discrepancy, the first of many, but the evidence helped Abbott justify a new product counterfeiting action (Abbott II) where the court ordered a seizure of defendant’s email server. That’s were the fun started. As Judge Bloom put it:

Magistrate Judge Lois Bloom (shown right) begins the Opinion by noting that the plaintiff’s motion for case ending sanctions “… presents a cautionary tale about how not to conduct discovery in federal court.” The issues started when defendant made its first electronic document production. The Electronically Stored Information was all produced in paper, as Judge Bloom explained “in hard copy, scanning them all together, and producing them as a single, 1941-page PDF file.” Opinion pg. 3. This is not what the plaintiff Abbott Labs wanted. After Abbott sought relief from the court the defendants on March 24, 2017 were ordered to “produce an electronic copy of the 2014 emails (1,941 pages)” including metadata. Defendant then “electronically produced 4,074 pages of responsive documents on April 5, 2017.” Note how the page count went from 1,942 to 4,074. There was no explanation of this page count discrepancy, the first of many, but the evidence helped Abbott justify a new product counterfeiting action (Abbott II) where the court ordered a seizure of defendant’s email server. That’s were the fun started. As Judge Bloom put it:

Once plaintiffs had seized H&H’s email server, plaintiffs had the proverbial smoking gun and raised its concerns anew that defendants had failed to comply with the Court’s Order to produce responsive documents in the instant action (hereinafter “Abbott I”). On July 12, 2017, the Court ordered the H&H defendants to “re-run the document search outlined in the Court’s January 17 and January 21 Orders,” “produce the documents from the re-run search to Abbott,” and to produce “an affidavit of someone with personal knowledge” regarding alleged technical errors that affected the production.³ Pursuant to the Court’s July 12, 2017 Order to re-run the search, The H&H defendants produced 3,569 responsive documents.

Opinion pg. 4 (citations to record omitted).

Too Late For Vendor Help and a Search Strategy Designed to Fail

After the seizure order in Abbott II, and after Abbott Labs again raised issues regarding defendants’ original production, Judge Bloom ordered the defendants to re-run the original search. Defendants then retained the services of an outside vendor, Transperfect, to re-run the original search for them. In supposed compliance with that order, the defendants, aka H&H, then produced 3,569 documents. Id. at 8. Defendants also filed an affidavit by Joseph Pochron, Director in the Forensic Technology and Consulting Division at Transperfect (“Pochron Decl.”) to try to help their case. It did not work. According to Judge Bloom the Pochron Decl. states:

… that H&H utilized an email archiving system called Barracuda and that there are two types of Barracuda accounts, Administrator and Auditor. Pochron Decl. ¶ 13. Pochron’s declaration states that the H&H employee who ran the original search, Andrew Sweet, H&H’s general manager, used the Auditor account to run the original search (“Sweet search”). Id. at ¶ 19. When Mr. Pochron replicated the Sweet search using the Auditor account, he obtained 1,540 responsive emails. Id. at ¶ 22. When Mr. Pochron replicated the Sweet search using the Administrator account, he obtained 1,737 responsive emails. Id. Thus, Mr. Pochron attests that 197 messages were not viewable to Mr. Sweet when the original production was made. Id. Plaintiffs state that they have excluded those 197 messages, deemed technical errors, from their instant motion for sanctions. Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Law at 9; Waters Decl. ¶ 8. However, even when those 197 messages are excluded, defendants’ numbers do not add up. In fact, H&H has repeatedly given plaintiffs and the Court different numbers that do not add up.

Moreover, plaintiffs argue that the H&H defendants purposely used search terms designed to fail, such as “International” and “FreeStyle,” whereas H&H’s internal systems used item numbers and other abbreviations such as “INT” and “INTE” for International and “FRL” and “FSL” for FreeStyle. Plaintiff’s Memorandum of Law at 10–11. Plaintiffs posit that defendants purposely designed and ran the “extremely limited search” which they knew would fail to capture responsive documents …

Opinion pgs. 8-9 (emphasis by bold added). “Search terms designed to fail.” This is the first time I have ever seen such a phrase in a judicial opinion. Is purposefully stupid keyword search yet another bad faith litigation tactic by unscrupulous attorneys and litigants? Or is this just another example of dangerous incompetence? Judge Bloom was not buying the ‘big oops” theory, especially considering the ever-changing numbers of relevant documents found. It looked to her, and me too, that this search strategy was intentionally design to fail, that it was all a shell-game.

This is the wake-up call for all litigators, especially those who do not specialize in e-discovery. Your search strategy had better make sense. Search terms must be designed (and tested) to succeed, not fail! This is not just incompetence.

The Thin Line Between Gross Negligence and Bad Faith

T he e-discovery searches you run are important. The “mistakes” made here led to a default judgment. That is the way it is in federal court today. If you think otherwise, that e-discovery is not that important, that you can just hire a vendor and throw stupid keywords at it, then your head is dangerously stuck in the sand. Look around. There are many cases like Abbott Laboratories, et al. v. Adelphia Supply USA.

he e-discovery searches you run are important. The “mistakes” made here led to a default judgment. That is the way it is in federal court today. If you think otherwise, that e-discovery is not that important, that you can just hire a vendor and throw stupid keywords at it, then your head is dangerously stuck in the sand. Look around. There are many cases like Abbott Laboratories, et al. v. Adelphia Supply USA.

I say “mistakes” made here in quotes because it was obvious to Judge Bloom that these were not mistakes at all, this was fraud on the court.

E-Discovery is about evidence. About truth. You cannot play games. Either take it seriously and do it right, do it ethically, do it competently; or go home and get out. Retire already. Discovery gamesmanship and lawyer bumbling are no longer tolerated in federal court. The legal profession has no room for dinosaurs like that.

E-Discovery is about evidence. About truth. You cannot play games. Either take it seriously and do it right, do it ethically, do it competently; or go home and get out. Retire already. Discovery gamesmanship and lawyer bumbling are no longer tolerated in federal court. The legal profession has no room for dinosaurs like that.

Abbott Labs responded the way they should, the way you should always expect in a situation like this:

Plaintiffs move for case ending sanctions under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 37 and invoke the Court’s inherent power to hold defendants in default for perpetrating a fraud upon the Court. Plaintiffs move to strike the H&H defendants’ pleadings, to enter a default judgment against them, and for an order directing defendants to pay plaintiffs’ attorney’s fees and costs, for investigating and litigating defendants’ discovery fraud.

Id.

Rule 37(e) was revised in 2015 to make clear that gross negligence alone does not justify a case-ending sanction, that you must prove bad faith. This change should not provide the incompetent with much comfort. As this case shows, the difference between mistake and intent can be a very thin line. Do your numbers add up? Can you explain what you did and why you did it? Did you use good search terms? Did you search all of the key custodians? Or did you just take the ESI the client handed to you and say thank you very much? Did you look with a blind eye? Even if bad faith under Rule 37 is not proven, the court may still find the whole process stinks of fraud and use the court’s inherent powers to sanction misconduct.

As Judge Bloom went on to explain:

Under Rule 37, plaintiffs’ request for sanctions would be limited to my January 17, 2017 and January 27, 2017 Orders which directed defendants to produce documents as set forth therein. While sanctions under Rule 37 would be proper under these circumstances, defendants’ misconduct herein is more egregious and goes well beyond defendants’ failure to comply with the Court’s January 2017 discovery orders. . . . Rather than viewing the H&H defendants’ failure to comply with the Court’s January 2017 Orders in isolation, plaintiffs’ motion is more properly considered in the context of the Court’s broader inherent power, because such power “extends to a full range of litigation abuses,” most importantly, to fraud upon the court.

Opinion pg. 5.

Judge Bloom went on the explain further the “fraud on the court” and defendant’s e-discovery conduct.

A fraud upon the court occurs where it is established by clear and convincing evidence “that a party has set in motion some unconscionable scheme calculated to interfere with the judicial system’s ability impartially to adjudicate a matter by . . . unfairly hampering the presentation of the opposing party’s claim or defense.” New York Credit & Fin. Mgmt. Grp. v. Parson Ctr. Pharmacy, Inc., 432 Fed. Appx. 25 (2d Cir. 2011) (summary order) (quoting Scholastic, Inc. v. Stouffer, 221 F. Supp. 2d 425, 439 (S.D.N.Y. 2002))

Opinion pgs. 5-6 (subsequent string cites omitted).

Kill All The Lawyers

The defendants here tried to defend by firing and blaming their lawyers. That kind of Shakespearean sentiment is what you should expect when you represent people like that. They will turn on you. They will use you for their nefarious ends, then lose you. Kill you if they could.

Judge Bloom, who was herself a lawyer before becoming a judge, explained the blame-game defendants tried to pull in her court.

Regarding plaintiffs’ assertion that defendants designed and used search terms to fail, defendants proffer that their former counsel, Mr. Yert, formulated and directed the use of the search terms. Id. at 15. The H&H defendants state that “any problems with the search terms was the result of H&H’s good faith reliance on counsel who . . . decided to use parameters that were less robust than those later used[.]” Id. at 18. The H&H defendants further state that the Sweet search results were limited because of Mr. Yert’s incompetence. Id.

Opinion pg. 9.

Specifically defendants alleged:

… the original search parameters were determined by Mr. Yert and that he “relied on Mr. Yert’s expertise as counsel to direct the parameters and methods for a proper search that would fulfill the Court’s Order.” Sweet Decl. ¶ 3–4. As will be discussed below, the crux of defendants’ arguments throughout their opposition to the instant motion seeks to lay blame on Mr. Yert for their actions; however, defendants cannot absolve themselves of liability here by shifting blame to their former counsel.

Opinion pg. 11.

Here is how Judge Bloom responded to this “blame the lawyers” defense:

Defendants’ attempt to lay blame on former counsel regarding the design and use of search terms is equally unavailing. It is undisputed that numerous responsive documents were not produced by the H&H defendants that should have been produced. Defendants’ prior counsel conceded as much. See generally plaintiffs’ Ex. B, Tr. Of July 11, 2017 telephone conference.

Mr. Yert was asked at his deposition about the terms that H&H used to identify their products and he testified as follows:

Q. Tell me about the general discussions you had with the client in terms of what informed you what search terms you should be using.

A. Those were the terms consistently used by H&H to identify the particular product.

Q. So the client told you that FreeStyle and International are the terms they consistently used to refer to International FreeStyle test strips; is that correct?

A. That’s what I recall.

Q. Did the client tell you that they used the abbreviation FSL to refer to FreeStyle?

A. I don’t recall.

Q. If they had told you that, you would have included that as a search term, correct?

A. I don’t recall if it was or was not included as a search term, sir.

Opinion pgs. 10-11.

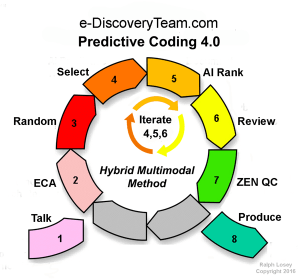

The next time you are asked to dream up keywords for searches to find your client’s relevant evidence, remember this case, remember this deposition. Do not simply use keywords that the client suggests, as the attorneys did here. Do not simply use keywords. As I have written here many, many times before, there is a lot more to electronic evidence search and review than keywords. This is the Twenty First Century. You should be using AI, specifically active machine learning, aka Predictive Coding.

You need an expert to help you and you need them at the start of a case, not after sanctions motions.

Judge Lois Bloom went on to explain that, even if defendant’s story of innocent reliance on it lawyers was true:

Judge Lois Bloom went on to explain that, even if defendant’s story of innocent reliance on it lawyers was true:

It has long been held that a client-principal is “bound by the acts of his lawyer agent.” Id. (quoting Link v. Wabash RR. Co., 370 U.S. 626, 634 (1962)). As the Second Circuit stated, “even innocent clients may not benefit from the fraud of their attorney.” Id. . . .

However, notwithstanding defendants’ assertion that the search terms “FreeStyle” and “International” were used in lieu of more comprehensive search terms at the behest of Mr. Yert, it is undisputed that Mr. Sweet, H&H’s general manager, knew that H&H used abbreviations for these terms. Mr. Sweet admitted this at his deposition. See Sweet Dep. 81:2-81:24, Mar. 13, 2018. . . . The Court need not speculate as to why defendants did not use these search terms to comply with defendants’ obligation to produce pursuant to the Court’s Order. Mr. Sweet, by his own admission, states that “on several occasions he contacted Mr. Yert with specific questions about whether to include certain emails in production.” Sweet Decl. ¶ 7. It is inconceivable that H&H’s General Manager, who worked closely with Mr. Yert to respond to the Court’s Order, never mentioned that spelling out the terms used, “International” and “FreeStyle”, would not capture the documents in H&H’s email system. Mr. Sweet knew that H&H was required to produce documents regarding International FreeStyle test strips, regardless of whether H&H’s documents spelled out or abbreviated the terms. Had plaintiffs not seized H&H’s email server in the counterfeiting action, plaintiffs would have never known that defendants failed to produce a trove of responsive documents. H&H would have gotten away with it.

Opinion pgs. 12-13.

Defendants also failed to produce any documents by three custodians Holland Trading, Howard Goldman, and Lori Goldman. Again, they tried to blame that omission on their attorney, who they claim directed the search. Oh yeah, for sure. To me he looks like a mere stooge, a tool of unscrupulous litigants. Judge Bloom did not accept that defense either, holding:

While defendants’ effort to shift blame to Mr. Yert is unconvincing at best, even if defendants’ effort could be credited, counsel’s actions, even if they were found to be negligent, would not shield the H&H defendants from responsibility for their bad faith conduct.

Opinion pgs. 19-20. Then Judge Bloom went on to cite the record at length, including the depositions and affidavits of the attorneys involved, to expose this blame game as a sham. The order then concludes on this point holding:

There is no credible explanation for why the Holland Trading, Howard Goldman, and Lori Goldman documents were not produced except that the documents were willfully withheld. Defendants’ explanation that there were no documents withheld, then that any documents that weren’t produced were due to technical glitches, then that the documents didn’t appear in Mr. Sweet’s original search, then that if documents were intentionally removed, they were removed per Mr. Yert’s instructions cannot all be true. The H&H defendants have always had one more excuse up their sleeve in this “series of episodes of nonfeasance,” which amounts to “deliberate tactical intransigence.” Cine, 602 F.2d at 1067. In light of the H&H defendants’ ever-changing explanations as to the withheld documents, Mr. Sweet’s inconsistent testimony, and assertions of former counsel, the Court finds that the H&H defendants have calculatedly attempted to manipulate the judicial process. See Penthouse, 663 F.2d 376–390 (affirming entry of default where plaintiffs disobeyed an “order to produce in full all of [their] financial statements,” engaged in “prolonged and vexatious obstruction of discovery with respect to closely related and highly relevant records,” and gave “false testimony and representations that [financial records] did not exist.”).

Opinion pgs. 22-23.

The plaintiff, Abbott Labs, went on to argue that “the withheld documents freed David Gulas to commit perjury at his deposition. The Court agrees.” Id. at 24. The Truth has a way of finding itself out, especially with competent counsel on the other side and a good judge.

With this evidence the Court concluded the only adequate sanction was a default judgment in plaintiff’s favor. Message to spoliating defendants, game over, you lose.

Based on the full record of the case, there is clear and convincing evidence that defendants have perpetrated a fraud upon the court. Defendants’ initial conduct of formulating search terms designed to fail in deliberate disregard of the lawful orders of the Court allowed H&H to purposely withhold responsive documents, including the Holland Trading, Howard Goldman, and Lori Goldman documents. Defendants proffered inconsistent positions with three successive counsel as to why the documents were withheld. Mr. Sweet’s testimony is clearly inconsistent if not perjured from his deposition to his declaration in opposition to the instant motion. Mr. Goldman’s deposition testimony is evasive and self-serving at best. Finally, Mr. Gulas’ deposition testimony is clearly perjured. Had plaintiffs never seized H&H’s server pursuant to the Court’s Order in the counterfeiting case, H&H would have gotten away with their fraud upon this Court. H&H only complied with the Court’s orders and their discovery obligations when their backs were against the wall. Their email server had been seized. There was no longer an escape from responsibility for their bad faith conduct. This is, again, similar to Cerruti, where the “defendants did not withdraw the [false] documents on their own. Rather, they waited until the falsity of the documents had been detected.” Cerruti.,169 F.R.D. at 583. But for being caught in a web of irrefutable evidence, H&H would have profited from their misconduct. . . .

The Court finds that the H&H defendants have committed a fraud upon the court, and that the harshest sanction is warranted. Therefore, plaintiffs’ motion for sanctions should be granted and a default judgment should be entered against H&H Wholesale Services, Inc., Howard Goldman, and Lori Goldman.

Conclusion

Attorneys of record sign responses under Rule 26(g) to requests for production, not the client. That is because the rules require them to control the discovery efforts of their clients. That means the attorney’s neck is on the line. Rule 26(g) does not allow you to just take a client’s word for it. Verify. Supervise. The numbers should add up. The search terms, if used, should be designed and tested to succeed, not fail. This is your response, not the client’s. You determine the search method, in consultation with the client for sure, but not by “just following orders.” You must see everything, not nothing. If you see no email from key custodians, dig deeper and ask why. Do this at the beginning of the case. Get vendor help before you start discovery, not after you fail. Apparently the original defense attorneys here did just what they were asked, they went along with the client. Look where it got them. Fired and deposed. Default judgment entered. Cautionary tale indeed.

Attorneys of record sign responses under Rule 26(g) to requests for production, not the client. That is because the rules require them to control the discovery efforts of their clients. That means the attorney’s neck is on the line. Rule 26(g) does not allow you to just take a client’s word for it. Verify. Supervise. The numbers should add up. The search terms, if used, should be designed and tested to succeed, not fail. This is your response, not the client’s. You determine the search method, in consultation with the client for sure, but not by “just following orders.” You must see everything, not nothing. If you see no email from key custodians, dig deeper and ask why. Do this at the beginning of the case. Get vendor help before you start discovery, not after you fail. Apparently the original defense attorneys here did just what they were asked, they went along with the client. Look where it got them. Fired and deposed. Default judgment entered. Cautionary tale indeed.

Posted by Ralph Losey

Posted by Ralph Losey

About the only way the requesting party, Yardi, can possibly get TAR disclosure in this case now is by proving the review and production made by Entrata was negligent, or worse, done in bad faith. That is a difficult burden. The requesting party has to hope they find serious omissions in the production to try to justify disclosure of method and metrics. (At the time of this order production by Entrata had not been made.) If expected evidence is missing, then this may suggest a record cleansing, or it may prove that nothing like that ever happened. Careful investigation is often required to know the difference between a non-existent unicorn and a rare, hard to find albino.

About the only way the requesting party, Yardi, can possibly get TAR disclosure in this case now is by proving the review and production made by Entrata was negligent, or worse, done in bad faith. That is a difficult burden. The requesting party has to hope they find serious omissions in the production to try to justify disclosure of method and metrics. (At the time of this order production by Entrata had not been made.) If expected evidence is missing, then this may suggest a record cleansing, or it may prove that nothing like that ever happened. Careful investigation is often required to know the difference between a non-existent unicorn and a rare, hard to find albino. Remember, the producing party here, the one deep in the secret TAR, was Entrata, Inc. They are Yardi Systems, Inc. rival software company and defendant in this case. This is a bitter case with history. It is hard for attorneys not to get involved in a grudge match like this. Looks like strong feelings on both sides with a plentiful supply of distrust. Yardi is, I suspect, highly motivated to try to find a hole in the ESI produced, one that suggests negligent search, or worse, intentional withholding by the responding party, Entrata, Inc. At this point, after the motion to compel TAR method was denied, that is about the only way that Yardi might get a second chance to discover the technical details needed to evaluate Entrata’s TAR. The key question driven by Rule 26(g) is whether reasonable efforts were made. Was Entrata’s TAR terrible or terrific? Yardi may never know.

Remember, the producing party here, the one deep in the secret TAR, was Entrata, Inc. They are Yardi Systems, Inc. rival software company and defendant in this case. This is a bitter case with history. It is hard for attorneys not to get involved in a grudge match like this. Looks like strong feelings on both sides with a plentiful supply of distrust. Yardi is, I suspect, highly motivated to try to find a hole in the ESI produced, one that suggests negligent search, or worse, intentional withholding by the responding party, Entrata, Inc. At this point, after the motion to compel TAR method was denied, that is about the only way that Yardi might get a second chance to discover the technical details needed to evaluate Entrata’s TAR. The key question driven by Rule 26(g) is whether reasonable efforts were made. Was Entrata’s TAR terrible or terrific? Yardi may never know.

The well-written opinion in

The well-written opinion in  The plaintiff, Yardi Systems, Inc, is the party who requested ESI from defendants in this software infringement case. It wanted to know how the defendant was using TAR to respond to their request. Plaintiff’s motion to compel focused on disclosure of the statistical analysis of the results, Recall and Prevalence (aka Richness). That was another mistake. Statistics alone can be meaningless and misleading, especially if range is not considered, including the binomial adjustment for low prevalence. This is explained and covered by my ei-Recall test. Introducing “ei-Recall” – A New Gold Standard for Recall Calculations in Legal Search –

The plaintiff, Yardi Systems, Inc, is the party who requested ESI from defendants in this software infringement case. It wanted to know how the defendant was using TAR to respond to their request. Plaintiff’s motion to compel focused on disclosure of the statistical analysis of the results, Recall and Prevalence (aka Richness). That was another mistake. Statistics alone can be meaningless and misleading, especially if range is not considered, including the binomial adjustment for low prevalence. This is explained and covered by my ei-Recall test. Introducing “ei-Recall” – A New Gold Standard for Recall Calculations in Legal Search –  Please, that is

Please, that is  The requesting party in Entrata did not meet the high burden needed to reverse a magistrate,s discovery ruling as clearly erroneous and contrary to law. If you are ever going to win on a motion like this, it will likely be on a Magistrate level. Seeking to overturn a denial and meet this burden to reverse is extremely difficult, perhaps impossible in cases seeking to compel TAR disclosure. The whole point is that there is no clear law on the topic yet. We are asking judges to make new law, to establish new standards of transparency. You must be open and honest to attain this kind of new legal precedent. You must use great care to be accurate in any representations of Fact or Law made to a court. Tell them it is a case of first impression when the precedent is not on point as was the situation in

The requesting party in Entrata did not meet the high burden needed to reverse a magistrate,s discovery ruling as clearly erroneous and contrary to law. If you are ever going to win on a motion like this, it will likely be on a Magistrate level. Seeking to overturn a denial and meet this burden to reverse is extremely difficult, perhaps impossible in cases seeking to compel TAR disclosure. The whole point is that there is no clear law on the topic yet. We are asking judges to make new law, to establish new standards of transparency. You must be open and honest to attain this kind of new legal precedent. You must use great care to be accurate in any representations of Fact or Law made to a court. Tell them it is a case of first impression when the precedent is not on point as was the situation in  To make new precedent in this area you must first recognize and explain away a number of opposing principles, including especially The Sedona Conference Principle Six. That says responding parties always know best and requesting parties should stay out of their document reviews. I have written about this Principle and why it should be updated. Losey,

To make new precedent in this area you must first recognize and explain away a number of opposing principles, including especially The Sedona Conference Principle Six. That says responding parties always know best and requesting parties should stay out of their document reviews. I have written about this Principle and why it should be updated. Losey,  Any party who would like to force another to make TAR disclosure should make such voluntary disclosures themselves. Walk your talk to gain credibility. The disclosure argument will only succeed, at least for the first time (the all -important test case), in the context of proportional cooperation. An extended 26(f) conference is a good setting and time. Work-product confidentiality issues should be raised in the first days of discovery, not the last day. Timing is critical.

Any party who would like to force another to make TAR disclosure should make such voluntary disclosures themselves. Walk your talk to gain credibility. The disclosure argument will only succeed, at least for the first time (the all -important test case), in the context of proportional cooperation. An extended 26(f) conference is a good setting and time. Work-product confidentiality issues should be raised in the first days of discovery, not the last day. Timing is critical. We have developed an

We have developed an

The Hybrid part refers to the partnership with technology, the reliance of the searcher on the advanced algorithmic tools. It is important than Man and Machine work together, but that Man remain in charge of justice. The predictive coding algorithms and software are used to enhance the lawyers, paralegals and law tech’s abilities, not replace them.

The Hybrid part refers to the partnership with technology, the reliance of the searcher on the advanced algorithmic tools. It is important than Man and Machine work together, but that Man remain in charge of justice. The predictive coding algorithms and software are used to enhance the lawyers, paralegals and law tech’s abilities, not replace them.

One Possible Correct Answer: The schedule of the humans involved. Logistics and project planning is always important for efficiency. Flexibility is easy to attain with the IST method. You can easily accommodate schedule changes and make it as easy as possible for humans and “robots” to work together. We do not literally mean robots, but rather refer to the advanced software and the AI that arises from the machine training as an imiginary robot.

One Possible Correct Answer: The schedule of the humans involved. Logistics and project planning is always important for efficiency. Flexibility is easy to attain with the IST method. You can easily accommodate schedule changes and make it as easy as possible for humans and “robots” to work together. We do not literally mean robots, but rather refer to the advanced software and the AI that arises from the machine training as an imiginary robot.

There is a new case out of Chicago that advances the jurisprudence of my sub-specialty, Legal Search.

There is a new case out of Chicago that advances the jurisprudence of my sub-specialty, Legal Search.  Judge Johnston begins his order in City of Rockford with a famous quote by

Judge Johnston begins his order in City of Rockford with a famous quote by

One of the main points Judge Johnston makes in his order is that lawyers should embrace this kind of technical knowledge, not shy away from it. As

One of the main points Judge Johnston makes in his order is that lawyers should embrace this kind of technical knowledge, not shy away from it. As  To be specific, the Plaintiffs wanted a test where the efficacy of any parties production would be tested by use of an Elusion type of Random Sample of the documents not produced. The Defendants opposed any specific test. Instead, they wanted the discovery protocol to say that if the receiving party had concerns about the adequacy of the producing party’s efforts, then they would have a conference to address the concerns.

To be specific, the Plaintiffs wanted a test where the efficacy of any parties production would be tested by use of an Elusion type of Random Sample of the documents not produced. The Defendants opposed any specific test. Instead, they wanted the discovery protocol to say that if the receiving party had concerns about the adequacy of the producing party’s efforts, then they would have a conference to address the concerns. One of the fundamental problems in any investigation is to know when you should stop the investigation because it is no longer worth the effort to carry on. When has a reasonable effort been completed? Ideally this happens after all of the important documents have already been found. At that point you should stop the effort and move on to a new project. Alternatively, perhaps you should keep on going and look for more? Should you stop or not?

One of the fundamental problems in any investigation is to know when you should stop the investigation because it is no longer worth the effort to carry on. When has a reasonable effort been completed? Ideally this happens after all of the important documents have already been found. At that point you should stop the effort and move on to a new project. Alternatively, perhaps you should keep on going and look for more? Should you stop or not? Once a decision is made to Stop, then a well managed document review project will use different tools and metrics to verify that the Stop decision was correct. Judge Johnston in City of Rockford used one of my favorite tools, the Elusion random sample that I teach in the e-Discovery Team TAR Course. This type of random sample is called an Elusion sample.

Once a decision is made to Stop, then a well managed document review project will use different tools and metrics to verify that the Stop decision was correct. Judge Johnston in City of Rockford used one of my favorite tools, the Elusion random sample that I teach in the e-Discovery Team TAR Course. This type of random sample is called an Elusion sample.

Judge Johnston’s Footnote Two is interesting for two reasons. One, it attempts to calm lawyers who freak out when hearing anything having to do with math or statistics, much less information science and technology. Two, it does so with a reference to

Judge Johnston’s Footnote Two is interesting for two reasons. One, it attempts to calm lawyers who freak out when hearing anything having to do with math or statistics, much less information science and technology. Two, it does so with a reference to  Although this is not addressed in the court order, in my personal view, no False Negatives, iw – overlooked documents – are acceptable when it comes to Highly Relevant documents. If even one document like that is found in the sample, one Highly Relevant Document, then the Elusion test has failed in my view. You must conclude that the Stop decision was wrong and training and document review must recommence. That is called an Accept on Zero Error test for any hot documents found. Of course my personal views on best practice here assume the use of AI ranking, and the parties in City of Rockford only used keyword search. Apparently they were not doing machine training at all.

Although this is not addressed in the court order, in my personal view, no False Negatives, iw – overlooked documents – are acceptable when it comes to Highly Relevant documents. If even one document like that is found in the sample, one Highly Relevant Document, then the Elusion test has failed in my view. You must conclude that the Stop decision was wrong and training and document review must recommence. That is called an Accept on Zero Error test for any hot documents found. Of course my personal views on best practice here assume the use of AI ranking, and the parties in City of Rockford only used keyword search. Apparently they were not doing machine training at all.

The inherent problem with random sampling is that the only way to reduce the error interval is to increase the size of the sample. For instance, to decrease the margin of error to only 2% either way, a total error of 4%, a random sample size of around 2,400 documents is needed. Even though that narrows the error rate to 4%, there is still another error factor of the Confidence Level, here at 95%. Still, it is not worth the effort to review even more sample documents to reduce that to a 99% Level.

The inherent problem with random sampling is that the only way to reduce the error interval is to increase the size of the sample. For instance, to decrease the margin of error to only 2% either way, a total error of 4%, a random sample size of around 2,400 documents is needed. Even though that narrows the error rate to 4%, there is still another error factor of the Confidence Level, here at 95%. Still, it is not worth the effort to review even more sample documents to reduce that to a 99% Level.

In

In  Judge Johnston takes an expansive view of the duties placed on counsel of record by Rule 26(g), but concedes that perfection is not required:

Judge Johnston takes an expansive view of the duties placed on counsel of record by Rule 26(g), but concedes that perfection is not required: Judge Johnston considered as a separate issue whether it was proportionate under Rule 26(b)(1) to require the elusion test requested. Again, the court found that it was in this large case on the pricing of prescription medication and held that it was proportional:

Judge Johnston considered as a separate issue whether it was proportionate under Rule 26(b)(1) to require the elusion test requested. Again, the court found that it was in this large case on the pricing of prescription medication and held that it was proportional:

It will be very interesting to watch how other attorneys argue City of Rockford. It will continue a line of cases examining methodology and procedures in document review. See eg., William A. Gross Construction Associates, Inc. v. American Manufacturers Mutual Insurance Co., 256 F.R.D. 134 (S.D.N.Y. 2009) (“wake-up call” for lawyers on keyword search);

It will be very interesting to watch how other attorneys argue City of Rockford. It will continue a line of cases examining methodology and procedures in document review. See eg., William A. Gross Construction Associates, Inc. v. American Manufacturers Mutual Insurance Co., 256 F.R.D. 134 (S.D.N.Y. 2009) (“wake-up call” for lawyers on keyword search);